An Interview with Director Alfonso Cuarón

January 17, 2013

Alfonso Cuarón is the Mexican director of a number of big Hollywood films, including: Children of Men, Y Tu Mamá También, and Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. A while ago, I noticed that Cuarón’s production company was called "Esperanto Filmoj." My curiosity was aroused and so I got in touch with Cuarón and had a lovely Skype conversation with him about Esperanto, hope, and the state of the world today. Here are some excerpts:

Sam Green: So what inspired the name of your company? Is there a story?

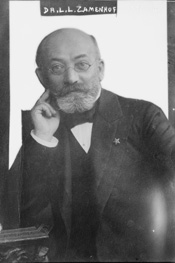

Alfonso Cuarón: I’d always been fascinated by Esperanto. I remember the first time that I came across Esperanto was through a Spanish writer called Miguel Unamuno, a Spanish writer of the first part of the 20th century. One of his characters was this eccentric anarchist who speaks Esperanto. Then I started getting the whole thing, the notion of Zamenhof, of this universal language that was going to bring the world together.

When I was looking for a name for this company––and I have done films in English and Spanish, and I wanted to do films in other languages, and I’ve done movies in different countries, and I believe that human beings are born human first, and afterward they stamp the passport. So I was looking for a name that advocates that sense of “universal language.” Whatever criticism I may have, my heart is with the notion and the idea of Esperanto.

SG: Yeah. It’s funny, I could sort of sense that just through Children of Men, obviously, and the short film, The Possibility of Hope, really moved me a lot in terms of being about hope and imagining a future, being able to imagine a radically different future. In a way, to me, that’s one of the things that Esperanto is about.

AC: I’m a very hopeful, very optimistic person. If anything, I’m pessimistic about the situation right now, but I’m optimistic about the future. The problem is I hate optimism that’s backwards. I think the first thing is to be very clear about the diagnostics, about what the situation is. Because if we’re not clear about that, how can we make any change?

The whole thing of Esperanto––and I know Esperanto has gone through its ups and downs––but there’s a purity about it. Because if it’s a utopia, it’s something very pure and very, in many ways handmade. It’s about people being able to communicate.

SG: Speaking of communicating, do you have anything you want to say to the Esperanto world?

AC: You know, I wish I could say it in Esperanto! My heart is with them. It’s one of those things in which... maybe there’s a way in which it would happen, in which the whole Esperanto movement would explode. I don’t know. It would be great––it’s a great idea, it’s a great notion. And also the fact that people are learning Esperanto, it makes me so happy to know that people actually follow the notion, and actually have a practice of the notion. And also, I’m happy to see how it’s kind of a spread-out community. It’s not surprising then, that the big ideologies persecuted Esperanto, no? Like in the last century, Nazism, and then Stalin decided that it was a danger.

SG: You know your Esperanto history!

AC: I know a little bit about it. I don’t know much. Again, I have a big sympathy for Esperanto, and again it came because the character... it was in my early teens that I read Niebla, this book by Unamuno, and I had such a sympathy for this––it was the old uncle of the love interest of the main character, this eccentric anarchist who was speaking Esperanto. And nobody understood him because he was saying everything in Esperanto. But the great thing is that everything he was saying in Esperanto, everything he was talking about was about the brotherhood of humanity. So for me they’re very connected, the idea of Esperanto and that notion.

SG: Hey, is there an office for your company somewhere that has “Esperanto Filmoj” on the front door?

AC: Ha! Where I was living, that was the official office for the company, and it was written on a piece of paper, hand-written with scotch tape. I moved from that place, but I’m going to look for a photo because I always liked to see it. I’ll have to look and send it to you if I can find it.

SG: that would be great. Thanks a lot for talking. It was a pleasure.

AC: No problem. Take care.